The Daughter Who Goes Swimming at Night | Devon Frederickson

I told my parents the fairytale version. I told them how Reed, my boyfriend of 11 years, opened the black box as if it were a clamshell with a fragile hinge. How he and I stood at the edge of a green lake cradled above treeline, so high in the Peruvian Andes that above us rose a gradient of mountains, then clouds, then mountains. How Reed lugged a bottle of sparkling wine to an elevation of 15,000 feet—because he was that kind of hero.

When I told my parents we were engaged, I left out the slippery part of the story. How, just one month before Reed asked to marry me, he proposed we open our relationship—though he’d left out the part about being in love with another woman, because at the time, he hadn’t realized love was what he was feeling. When, eventually, I told him we could try it, I left out how, after I’d read the non-monogamy book he’d recommended, I’d hurled it across our bedroom and it made a satisfying smack against the opposite wall, accordioning the pages.

During our 13-month engagement, I told my parents only what I thought they wanted to hear: that we would marry under the giant oak tree near Reed’s parents’ property, that we would serve home-baked pies during the reception, that I would wear flowers in my hair. I told them the bright, buzzing stuff. I wanted to spare them. Or perhaps I wanted to spare myself from judgment, from my parents assuming my relationship was too unconventional, too risky—too doomed. Perhaps I was afraid they would assume it meant something was wrong, or that by telling them, I would have to admit to myself that something was.

Children learn to hide their pain from their parents. Maybe this is to spare parents the ache of knowing they can’t protect their children. In my case, maybe I’d also wanted to hide from my parents how much pain Reed and I were both capable of causing.

I didn’t know how to handle Reed being in love with another woman, so I slept with other men and women to distract myself. Reed didn’t know how to handle me sleeping around, so he turned his attention more toward the other woman he loved.

During our wedding ceremony, Reed and I polished the tarnish off our story until it glinted in the sun on a bright September day, our speeches punctuated by acorns thudding into dry, prairie grass. With silk roses in my hair and pheasant feathers pinned to Reed’s lapel, we stood at the base of the old oak tree. In front of dozens of friends and family, we explained the ways we loved each other, and we meant every word. There were things we left unsaid, though, because we didn’t know how to explain them.

Reed and I returned weather worn from our honeymoon to Spain. To my parents, I divulged details that would delight them, because wouldn’t they want to hear only the good parts? I told them about the lemon peel scent of citrus groves, the red tinge of fall spreading across mountain forests, and the twisting limbs of ancient olive groves. I didn’t mention my broken heart. How, throughout our honeymoon, Reed hadn’t stopped texting the other woman he loved. How I’d shoved the word “divorce” toward him like a stack of poker chips; I was all in, I just needed him to show me his hand. How he and I had sat in silence through a plane ride, holding hands, palms sweating, both of us wondering whether we were nearing the end of our marriage, mere weeks after our wedding.

On a gray morning during our honeymoon, I took my sorrow to the sea. With dark clouds hanging heavy over the Mediterranean, I wandered to a limestone cliff and sat on the edge of it, hugged my knees to my chest, and cried. I stayed there long after it started to rain.

That evening, Reed and I sat on the couch of our rental apartment as a storm threw gusts of wind against the windows, rattling the glass. Candle flames shuddered. Restless, I set my book down, turned to Reed, and asked if he would go with me into the storm.

Toting a bottle of red wine and two glasses, I led him to the same limestone cliff I’d visited that morning. We sat on a rock wet from rain, our knees touching. I accidentally knocked over one of the wine glasses, shattering it. Gently, Reed brushed my hand away, gathering the pieces in the dark so I wouldn’t get hurt. Passing the remaining glass between us, we watched the storm. All around us: darkness—though we’d come seeking light. A terrible rumble preceded each flash of lightning, but then the world was made bright again, lit up like a plea to be seen.

“The thing that sucks about being married,” my sister-in-law said, “is that you’re stuck with the person.” It was some months after the wedding, and she and I were walking the dirt road past the old oak, its branches winter-bare. “A marriage is like a tree,” she continued. “You don’t have as many opportunities to grow out, so you have to grow down and take deeper roots.”

As she spoke, I considered my relationship, and whether its openness had given us so much room to stretch our limbs that we weren’t exerting energy into growing down anymore, into our relationship—into ourselves. However, when I considered returning to monogamy, I was reluctant. It wasn’t that I was unwilling to stop dating other people if it would allow my marriage some relief, or that I thought Reed wouldn’t agree to stop seeing the other woman if I asked him to. I was afraid that, even if we made those changes, it wouldn’t work.

A couple of months later, like lightning lopping branches off a tree, a global pandemic struck.

Within this new reality, I couldn’t date other people without compromising the safety of our household. Because of a health condition, the other woman limited her contact with Reed.

With our branches cleaved, we were forced to grow down. Even while the world stormed around us, we dug in.

Several months into the pandemic, Reed and I drove to a shore, paddled to an island, then hiked to a remote beach. Through coastal mist, I watched him stride along the wrack line of a salt marsh. He was whistling a tune, his boots squelching in mud. He scooped clams and steamed them, plucked oysters from the muck and roasted them, cut thistles and boiled the stems. Every so often, he glanced over at me and beamed a smile. Watching him, the love I felt was the wild, rooted kind.

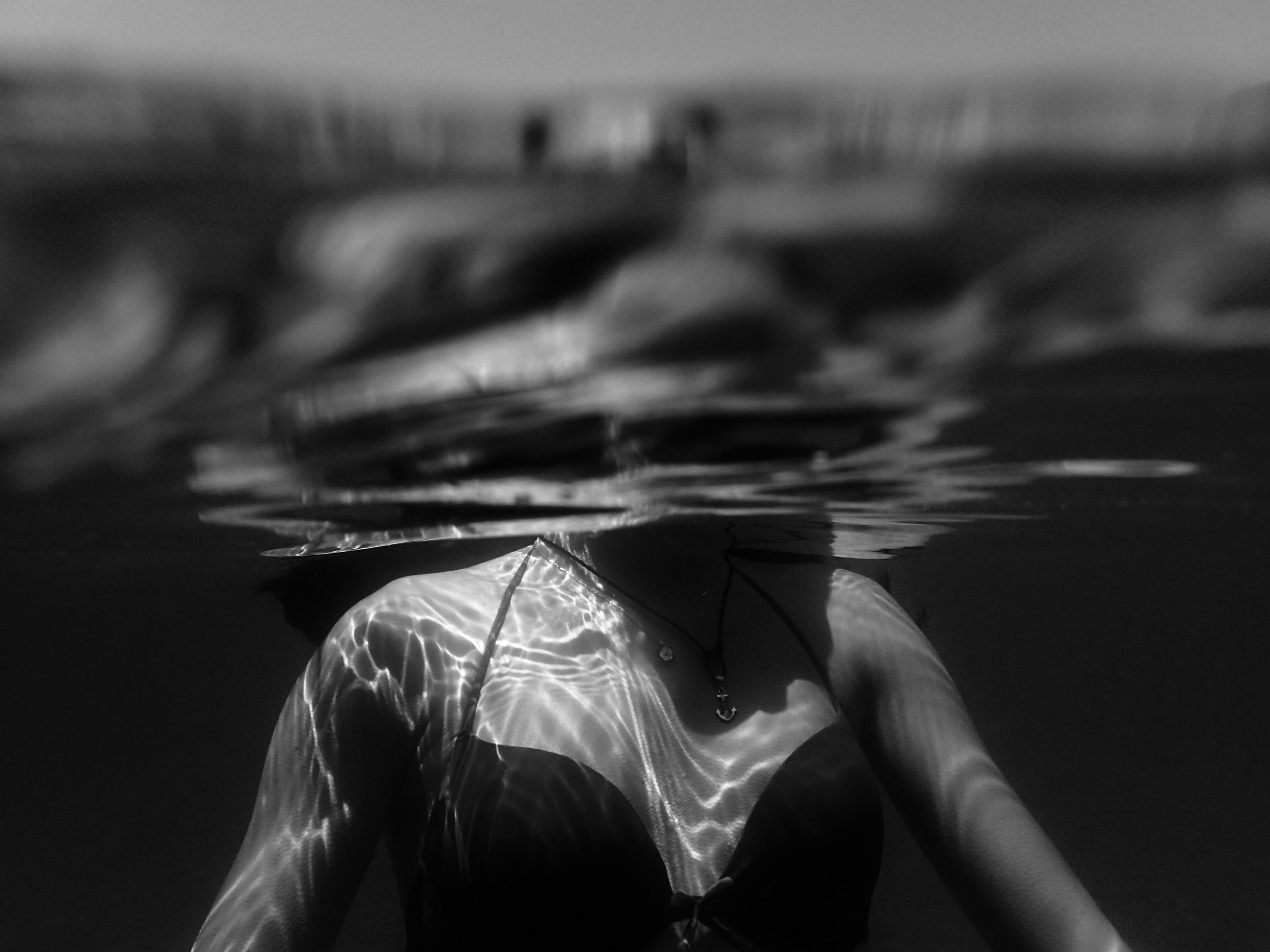

Six months into the pandemic, I visited my parents at the lake house they’d inherited from my grandmother. One night, wearing a face mask and swimsuit, I walked past my mom. She followed me down to the shore. Though I was 33, I groaned in frustration like a teenager; I’d been looking forward to swimming alone, and she was infringing on my solitude. I slipped off my sandals and mask then waded into the blue-black water, ignoring my mom standing on the shore behind me. I swam out—farther, farther—into darkness.

Under a moonless sky, bats swung through the air, their bodies darting over my head. Strands of slippery reeds wrapped around my ankles. Even without looking back, I knew my mom was there, watching me, making sure I would be OK—as if the bats might bite or the reeds might pull me under. Despite my annoyance, I smiled then, because I remembered how my dad had done the same thing the previous night. I’d gone for a swim, and he’d stood on the shore watching me, as they’d both done many times during my childhood. My parents simply could not help themselves; their instinct to protect overrode my annoyance.

After returning to the beach, I toweled myself off. Though I was still intent on ignoring my mom, I laughed a little.

“Sorry,” she said. “But I’ll always be your mother.”

Nearly three years after entering non-monogamy, I considered telling my parents about my open marriage—now that my relationship seemed lighter, more solid. As if Reed and I could call ourselves a “success story” at this sort of thing. As if the current state of our relationship was enough to convince my parents to not dwell on our past pain. As if there wouldn’t be future pain. As if our story had somehow reached a resolution, even though the hard work was still ahead of us. After years of keeping our open arrangement a secret, I had become less concerned about the ways they would worry if I told them. Now, I was more concerned about what they might miss if I didn’t.

I pictured my parents watching me from shore—how they’d stood sentinel. I’d originally thought it was out of concern for my safety, to make sure nothing happened to me. I now suspected they also wanted to bear witness. They wanted to see their daughter move through the dark water—perhaps so they could marvel at having created a person who would do such a thing. Their pure, quiet interest reminded me that my parents are still learning who I am.

I had long worried that if my parents knew the truth about my relationship, they might not recognize me. However, I began to wonder what would happen if I didn’t allow them to see the person I was becoming.

Eventually, I told them. I told them because I realized my parents want to know all of me, even if they can’t protect me, their daughter who goes swimming at night. They will continue to stand on the shore, whether I want them to or not, watching me swim farther into the darkness, squinting their eyes to keep on seeing me.

Devon Fredericksen is an independent environmental journalist and the author of several books, including How to Camp in the Woods and 50 Classic Day Hikes of the Eastern Sierra. Her work has been published in The Atlantic, High Country News, bioGraphic, Guernica, Sonora Review, and Switchyard, among other publications. She lives in Portland, Oregon.